A Family Affair

by David E. Tripp

“An English Gentleman, of family and fortune, of the name of Strickland .... will, I expect, be at Mt. Vernon before I shall. If this is the case ... I request you treat him with all the attention and civility in your power.

He is a plain man in his dress and manners.... ”

— George Washington to William Pearce, March 29, 1795

|

In October, 1964, an auction at Christie’s in London of a portion of the coin collection belonging to the 4th Baron St. Oswald of Nostell was highlighted by a section containing 30 United States coins struck in 1794-1795. The coins, with a face value of $6.72 were, for the most part, in nearly pristine condition. The announcement of the sale created a furor of interest in the United States, and a number of eminent collectors and dealers made their way across the Atlantic to examine the coins and bid at the auction. In October, 1964, an auction at Christie’s in London of a portion of the coin collection belonging to the 4th Baron St. Oswald of Nostell was highlighted by a section containing 30 United States coins struck in 1794-1795. The coins, with a face value of $6.72 were, for the most part, in nearly pristine condition. The announcement of the sale created a furor of interest in the United States, and a number of eminent collectors and dealers made their way across the Atlantic to examine the coins and bid at the auction.

Over the next three decades, an undocumented theory that an ancestor of the auction’s consignor, also named Major the Lord St. Oswald, M.C. (or Sir Rowland Winn), had acquired the coins at the Philadelphia Mint in the years of manufacture and that they had descended in the family found general, unquestioned, acceptance.

In 1994, an article dismissed this hypothesis. It noted that there was no “Major the Lord St. Oswald, M.C.” in 1794-1795 (the title didn’t exist until 1885 nor, until 1914, did the military decoration, M.C. [Military Cross]). The article posited (based on correspondence with the then Lord St. Oswald [family name, Winn]) that no member of the Winn family had visited the United States in the 18th century, and that “It now appears certain the United States coins in the 1964 sale were not obtained directly from the Mint by a St. Oswald [Winn] family member.”

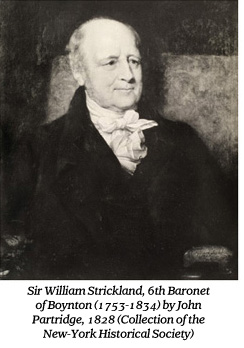

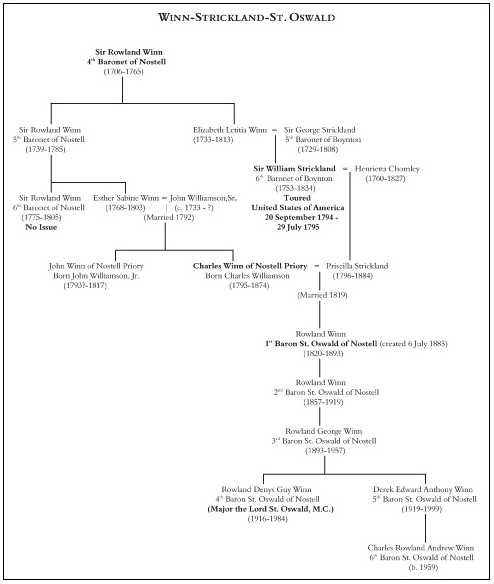

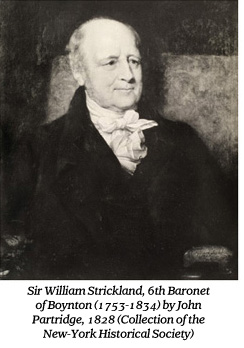

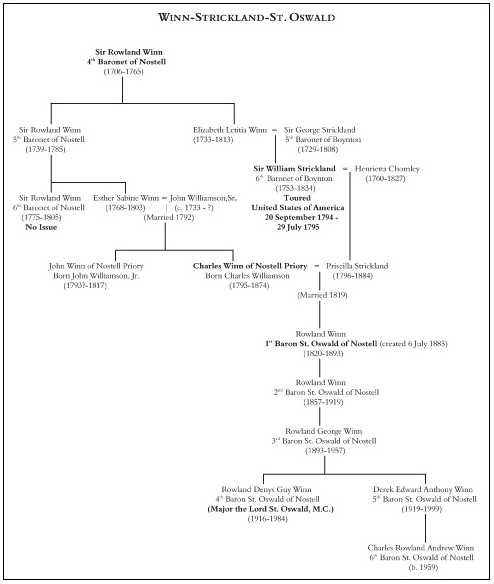

However, new research, archival, numismatic, and genealogical, has produced a compelling body of circumstantial evidence that the St. Oswald coins were originally acquired by William Strickland (1753-1834), later 6th Baronet of Boynton. He paid a lengthy visit to the United States in 1794-1795, and was a member of the Winn family through which the coins descended until their sale.

Strickland, a nephew of Sir Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet of Nostell (1739-1785), was a coin collector himself, and “actively expanded” both his father’s coin collection and library “rich in numismatic texts.” Following Strickland’s death in 1834, “[t]he coins duly made their way to Nostell.” They were acquired by Strickland’s son-in-law (and cousin) Charles Winn, from whom they passed to his son, Rowland Winn, later 1st Baron St. Oswald of Nostell (William Strickland’s grandson).

In 1981 and 1992, additional groups of coins from the collection were removed from Nostell Priory and sold at Christie’s. The second parcel contained two 1794 half cents and an additional two 1794 cents, all well preserved, together with a circulated 1793 Chain cent, and approximately 50 United States colonial and post-colonial coins. These were the type of coins that would have been circulating during Strickland’s tour of America, and together the contents of the 1964 and 1992 offerings not only provide a fascinating numismatic sidelight, but more fully cement the identity of the original acquirer.

William Strickland’s ten month tour of the United States in 1794-1795 was remarkable. Not only did he spend over four months in the nation’s capital, Philadelphia, but he had a wide circle of acquaintances in America’s governing circles; he knew a good number of the Founding Fathers socially, was a guest at both Mount Vernon and Monticello and became, upon his return to England, a correspondent of both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

|

William Strickland and his Tour of the

United States of America

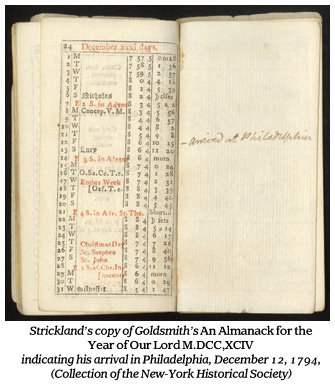

William Strickland was an accomplished man with a wide spectrum of interests and talents. A gentleman farmer, antiquary, artist, naturalist, scientist, and collector, he first set foot in New York on September 20, 1794, a sunny Saturday. His journey aboard the American merchantman, Fair American, had taken two months, during which time the ship had once been boarded and rummaged by seamen from the British frigate Thetis.

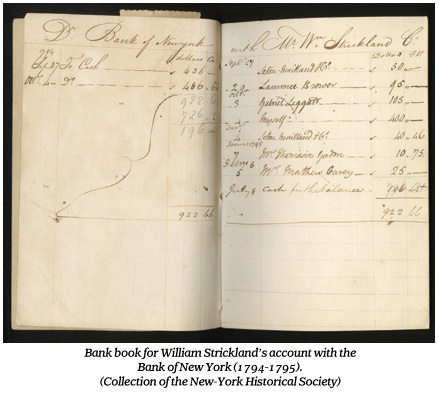

Upon his arrival in New York, Strickland was immediately taken under the wing of “Mr: [William] Seton, a Gentleman of the first respectability in the place, on whom I [was] to rely for much assistance while in this country.” Seton (1746-1798), the first Cashier of the Bank of New York, later served on its board of directors, and had assisted Alexander Hamilton’s research for one of the United States Mint’s birth certificates, the 1791 report, “On the Establishment of a Mint.”

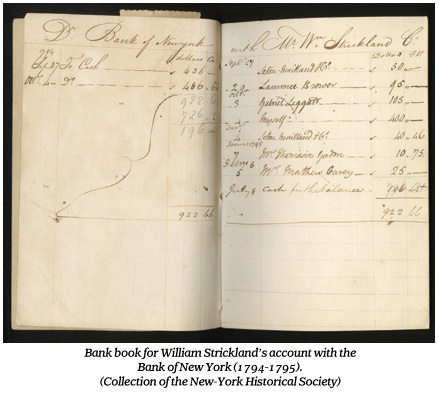

Seton found Strickland lodging and introduced him to the British Minister Plenipotentiary, George Hammond, who, Strickland noted, didn’t much care for the country to which he had been posted. On September 27, 1794, Strickland opened an account at the Bank of New York indicating that he had brought some 200 guineas for his expenses.

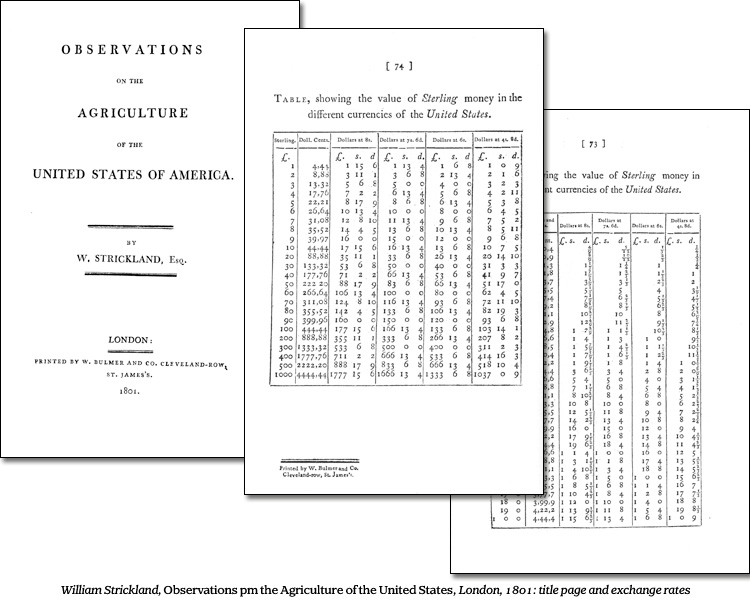

On October 6th, Strickland began a 900-mile journey on horseback from New York City to Saratoga, to Albany, then through Connecticut to Boston, where he saw “the unfortunate fields of Bunker’s Hill,” returning via the coast to New York by the end of November. An outgoing and insatiably curious man who was armed with letters of introduction to a panoply of America’s leading citizens, he nevertheless felt that, “being an Englishman, is the best passport any one can have in this country,” and so he met, spoke, and learned about America from citizens in all walks of life. He made notes on American industry (he visited cotton and wool mills, glass works, sawmills, and the “foundry for casting brass artillery” at Springfield), agriculture (he was not impressed), real estate (prime building lots in Philadelphia were “£60. per foot in front”), wages, law-making, and jurisprudence. Many of these were later published in his Observations on the Agriculture of the United States of America, London, 1796 and his Journal of a Tour in the United States of America: 1794-1795, New York, 1971 (the Journal ends in November 1794 in Boston, and the rest of Strickland’s tour must be reconstructed from a variety of sources, some as yet unpublished).

During the New York leg of his travels he met with Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, and stayed with founding father, Chancellor Robert Livingston at Clermont, from which he departed “with regret.” In Connecticut he was given a tour of the Hartford environs by then member of Congress, Jeremiah Wadsworth, who introduced him to the state’s governor and signer of the Declaration of Independence, Samuel Huntington. And in Massachusetts Strickland presented his letters of introduction to Vice President John Adams; although their meeting at this time was short. Strickland later (c. 1796-1797) wrote to a friend regarding Adams election to the presidency that, “I know him well and believe him worthy to sit in the Chair in which Washington proceede[d him].”

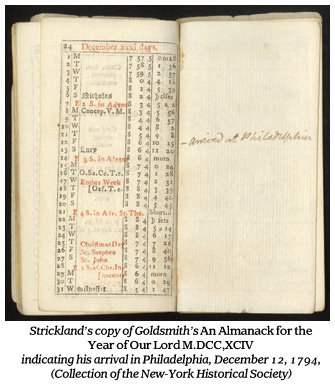

Strickland arrived in Philadelphia in mid-December where, he wrote, having “already become acquainted with some of the leading characters of the country [....] I have every reason to believe I shall spend the next three months in the most interesting society, of which I ever did or probably ever shall make a part.” He was right.

By December 22, 1794 Strickland had already “once attended” a debate in Congress, and while waiting “for my cloaths [to] arrive from New York” so he could present his letters of introduction to President Washington, reported that he had already “experience[d] much hospitality.”

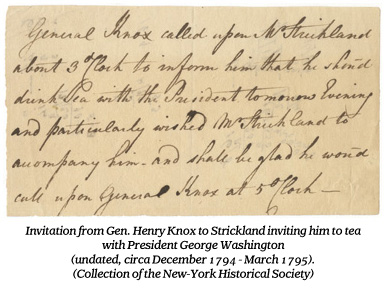

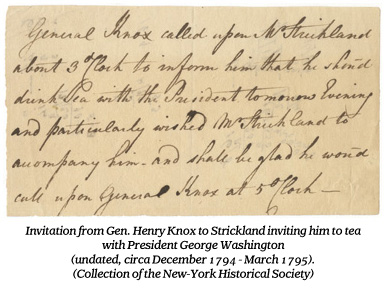

George Washington appears to have taken a liking to his fellow farmer, Strickland, who had brought “turnip and many other seeds from England” for Washington to experiment with at Mount Vernon. Although it is unknown how often their paths crossed during Strickland’s initial three-and-a-half months in Philadelphia, on one (undated) occasion, “General Knox called upon Mr. Strickland about 3 o’Clock to inform him that he should drink Tea with the President tomorrow Evening and particularly wished Mr. Strickland to accompany him.”

Spring arrived and Strickland prepared to continue his tour. The President invited Strickland to visit Mt. Vernon, and also personally wrote seven letters of introduction on his behalf to, among others: the Governors of Maryland and Virginia, Revolutionary hero, General Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, and Thomas Jefferson, then in retirement from government at Monticello. Washington asked his former secretary of state to extend his “civilities and attention” as Mr. Strickland’s “merits, independent of the recommendation of Sir Jno. Sinclair, will entitle him to them.”

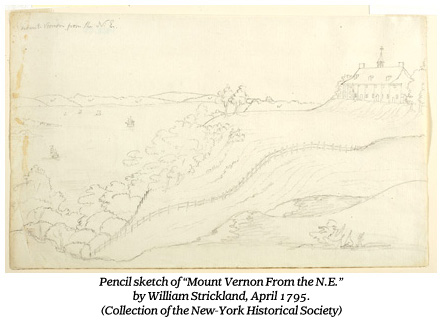

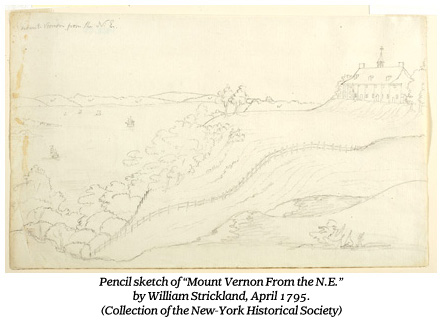

On April 4, 1795, “w. drifts of snow lying in the road sides,” Strickland headed south. He arrived at Mount Vernon on April 16, where he made drawings of the house and the view from its portico, and noted “much thunder and lightning most of the night.” By May 14, Strickland was at Monticello, where Thomas Jefferson made him welcome.

The two men, both polymaths, discussed a wide range of common interests, from plow mould boards (a subject on which  Jefferson also consulted with David Rittenhouse [the first Director of the Mint]), to agriculture, to the introduction of the turkey to England. The men parted and maintained a cordial correspondence on all manner of subjects, even after Jefferson returned to public life both as vice president and president. Jefferson also consulted with David Rittenhouse [the first Director of the Mint]), to agriculture, to the introduction of the turkey to England. The men parted and maintained a cordial correspondence on all manner of subjects, even after Jefferson returned to public life both as vice president and president.

His southern tour over, Strickland headed back to Philadelphia for a week before briefly returning to New York where he closed his account with the Bank of New York on July 8th, taking “Cash for the balance” in the amount of $196.45. Strickland’s final stop was again Philadelphia, where he spent his last week and a half in the United States.

On July 15, Washington sent Strickland a letter asking him to carry correspondence on his behalf to Sir John Sinclair; he ended his note by adding: “I sincerely wish you a safe & pleasant passage; & a happy meeting with your family & friends in England.”

William Strickland “Embarked [in Philadelphia] onboard the Camilla [,] Captain Irwin for Falmouth” on July 29, 1795, and he arrived in England after “a short, but rough and consequently not agreeable passage” on September 1st.

In the years to come, in addition to Washington (who wrote him a particularly lengthy letter on July 15, 1797 from “under my own vine and Fig tree” closing that “Mrs Washington feels the obligation of your polite remembrance of her”) and Jefferson, Strickland kept in touch with a number of his new friends in America. His extant letter book includes missives to Robert Livingston, John Murray, William Seton, Caleb Lownes, (a merchant in Philadelphia who supplied “Bar Iron & Moulds” to the Philadelphia Mint in 1793 and 1795, and was the first administrator of the Walnut Street Prison), and fellow Englishman John Guillemard (in Philadelphia). To Guillemard, on February 9, 1800, following the news of George Washington’s death, Strickland wrote a revealing letter that conveys a sense of the mutual esteem Washington and he appear to have had for one another:

“Your letter of the 4th Novr. contained a paragraph with which I could not but be flatter’d in finding myself remember’d with respect at Mount-Vernon; alas! I had scarcely receiv’d your letter before an account arriv’d of the death of him by whom I was so much honour’d for I must ever hold it the highest honour of my life to have been thought well of by him whom the world allows to have passed and long & arduous life without having committed a fault.”

|

The Strickland-Winn-St. Oswald Collections

Thirteen years after William Strickland’s return to England, his father, the 5th Baronet of Boynton, died and he ascended to the title. As previously noted, he inherited his father’s varied collections including coins and a library that contained a significant group of works on numismatics and enlarged both. He acquired coins from the tenth century Bossall/Flaxton hoard, which was found on his brother-in-law’s property, and in 1809, he gave a Samanid dirham from the find to the renowned numismatist William Marsden; other coins from the hoard were published in the British Journal of Numismatics in 1960-61, and sold in the Christie’s sale in 1964. Thirteen years after William Strickland’s return to England, his father, the 5th Baronet of Boynton, died and he ascended to the title. As previously noted, he inherited his father’s varied collections including coins and a library that contained a significant group of works on numismatics and enlarged both. He acquired coins from the tenth century Bossall/Flaxton hoard, which was found on his brother-in-law’s property, and in 1809, he gave a Samanid dirham from the find to the renowned numismatist William Marsden; other coins from the hoard were published in the British Journal of Numismatics in 1960-61, and sold in the Christie’s sale in 1964.

In 1819, another coin collector, Charles Winn of Nostell, became Strickland’s son-in-law. The two men not only had shared interests but a common ancestor as well, Sir Rowland Winn, 5th Baronet of Nostell was Sir William Strickland’s uncle, and Charles Winn’s grandfather.

Charles Winn, a voracious collector (a “collectionneur enragé”) in many fields, was a most unlikely inheritor of the renowned country house, Nostell Priory (which was partly designed by Robert Adam and contains about 100 works commissioned directly from the great cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale, including a coin cabinet [1767] from which the coins were removed for auction in 1964). Winn’s mother had caused a scandal by marrying a baker, by whom she had three children. Upon her death, the children became the wards of their uncle, the 6th Baronet of Nostell who died childless two years later. The children changed their name to Winn and the eldest, John, succeeded to Nostell (but not the title); upon his untimely death in 1817, his younger brother Charles (who served as the Rector of Wragby) inherited Nostell Priory.

When William Strickland died in 1834, his coin collection (some of whose coins were accompanied by his own “very instructive” remarks) and portions of his library, notably the numismatic books, were acquired, at least in part by purchase (a balance paid of £166-10-0 was recorded in July 1836) by his son-in-law, Charles Winn, father of the 1st Baron St. Oswald of Nostell Priory. |

The William Strickland– Nostell Priory – Lord St. Oswald United States Coin Collection

Two groups of United States coins from Nostell Priory were sold at Christie’s. The first portion sold in 1964 is justifiably the most renowned, but the overall importance of the collection does not fully come into focus until it is combined with the second parcel, sold in 1992 (and today barely known), the newly suggested provenance, and knowledge of William Strickland’s visit to the United States in 1794-1795.

The combined collection of some 84 coins, of which most of the 34 1794-1795 federal issues were essentially as made (there was also a single 1793 circulated Chain cent), provides an excellent cross section of the kind of American coins that would have been circulating (and available fresh from the Mint) during William Strickland’s tour. Of the 49 pre-federal issues, there are examples from every state through which Strickland passed with the exception of Maryland. They are for the most part worn, and whether they were accumulated as pocket change or consciously collected is a matter of debate; probably it was a little of both, as the fairly broad diversity of type indicates the acquisition by someone with the practiced eye of a coin collector, as Strickland is known to have been.

A close examination of the 1794-1795 Philadelphia Mint issues is even more revealing. The St. Oswald Collection only contained varieties or denominations that would have been available to William Strickland during his time in America between September 20, 1794, and July 29, 1795.

The majority of the coins in effectively “new” condition were produced after October 15, 1794 and nearly half the collection’s 24 1794 large cents were from deliveries made while Strickland is known to have been in Philadelphia in December 1794.

Bearing in mind that Strickland set sail for England on July 29, 1795, of particular interest is what 1795 coins the St. Oswald collection lacked: there were no examples of half eagles (first delivered July 31, 1795); no eagles (first delivered September 22, 1795); no Draped Bust dollars (first believed to have been produced around the beginning of October 1795); nor half cents or cents (which were not produced until the last two months of the year). The absence of 1795 half dimes, which theoretically he could have obtained is inexplicable, but for the majority of types and denominations produced in 1795 the St. Oswald collection is notably missing all the 1795-dated coins which were produced after William Strickland had left for home.

Conclusion:

That such an astonishing group of American coins produced at the Philadelphia Mint in 1794-1795, in near perfect condition, survived in the collection of a single family for over a century-and-a-half is, on its own, remarkable. But even more astonishing is that there is now demonstrable evidence that identifies which of their ancestors (a coin collector) toured the United States of America and was in Philadelphia in 1794-1795.

The importance of the 1794-1795 coins from the William Strickland-Charles Winn-Lord St. Oswald-Nostell Priory Collection cannot be understated. They were originally acquired in the year of issue, not merely by some casual tourist, but by a truly remarkable man: a vitally interested amateur, a numismatist no less, who traveled in the august company of some of our nation’s Founding Fathers, including a number who were integral to the birth of the United States Mint. The original “Lord St. Oswald” theory, once discarded, may now be said to have been not so wide of the mark, and that with William Strickland as the original acquisitor, the provenance is even richer and more important than previously imagined.

It was, very much, a family affair.

Note: The above note is an abbreviated version of a forthcoming article. |

Reconstructed Collection of United States Colonial, Post-Colonial,

and Federal Coins removed from Nostell Priory

(Sold Christie’s 1964 & 1992) |

Massachusetts:

1662 Oak Tree Twopence (1992)

1652 Oak Tree Sixpence (1964)

1652 Pine Tree Shilling, Large (1964)

1652 Pine Tree Shillings, Small [2] (1964)

New Jersey:

St. Patrick Farthings [3] (1992)

St. Patrick Halfpenny (1992)

American Plantation:

ND 1/24 Part Real (1992)

Rosa Americana:

ND Twopence (1964)

1723 Twopence (1964)

Woods Hibernia:

1723 Halfpennies [4] (1992)

1723 Farthing (1992)

Virginia:

1773 Halfpenny (1992)

|

Elephant Token:

ND Halfpenny (1992)

Hibernia-Voce Populi:

1760 Halfpennies [5] (1992)

Nova Constellatio:

1783 Pointed Rays (1992)

1785 Pointed Rays (1992)

Massachusetts:

1787 Cent (1992)

1788 Cents [2] (1992)

Connecticut:

1785 Bust Right (1992)

1787 Bust Left [7] (1992)

1788 Bust Right (1992)

New York:

1787 Nova Eborac (1992)

|

New Jersey:

1786 (1992)

1787 [4] (1992)

Worn (1992)

Vermont:

1787 Bust Right (1992)

Talbot, Allum & Lee

1794 Cent, New York (1964)

Washington Pieces:

1791 Cent, Small Eagle (1964)

1795 Liberty & Security Penny

Asylum Edge (1992)

Federal:

1794 Half Cents [2] (1992)

1793 Chain Cent AMERICA (1992)

1794 Cents [24] (1964[22]; 1992 [2])

1795 Half Dollars [3] (1964)

1794 Silver Dollars [2] (1964)

1795 Silver Dollars Flowing Hair [3] (1964) |

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to acknowledge with profound thanks the assistance, guidance, suggestions, and reminiscences of: Sarah Acton & Sam Bartle (East Riding Archive); Deborah Coy (Christie’s); Matthew Di Biase (National Archives and Records Administration); Tom Eden (Morton & Eden); Richard Falkiner (formerly of Christie’s); Adrian Green (Durham University); David Hill (American Numismatic Society); Edward Potten (Joint Head of Special Collections, Cambridge University Library); Michael Ryan, Edward O’ Reilly, Tammy Kiter (New-York Historical Society); Robert Scott; Eric Streiner; David Sundman;Nicola Thwaite (National Trust).

Select Bibliography:

Bowers, Q. David, Silver Dollars and Trade Dollars of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia,1993.

Breen, Walter, Walter Breen’s Encyclopedia of United States and Colonial Proof Coins, 1977.

Breen, Walter, Walter Breen’s Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins, 1988.

Breen, Walter, Walter Breen’s Encyclopedia of United States Large Cents, in collaboration with Del Bland, Edited by Mark Borckardt, 2000

Brockwell, M.W., Catalogue of the Pictures and other Works of Art in the Collection of Lord St. Oswald at Nostell Priory,1915.

Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd, Catalogue of English, Foreign and Important American Coins: The Property of Major the Lord St. Oswald, removed from Nostell Priory, Wakefield, Yorkshire, October 13, 1964.

Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd, Coins and Medals, 14 April 1981.

Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd, Coins and Medals, 18 February 1992.

Fitzpatrick, J.C., Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, vol 34, 1940.

Hodder, M., “Who Was Major the Lord St. Oswald?”, The Asylum, vol. xii, no. 4, 1994, pp. 3-7.

New-York Historical Society, Sir William Strickland Papers (1793-1827).

Potten, E., The Cultivated Eye: Books and Reading at Nostell Priory, 2007.

Potten, E., “Beyond Bibliophilia: Contextualizing Private Libraries in the Nineteenth Century,” Library and Information History, Vol 31, No. 2, May 2015, pp. 73-94.

Raikes, S., ‘“A cultivated eye for the antique”: Charles Winn and the Enrichment of Nostell Priory in the Nineteenth Century,’ Apollo, 2003 (reproduced online at www.freelibrary.com).

Strickland, W., Observations on the Agriculture of the United States of America, 1801; re-printed as part of the N-YHS edition of Stickland’s Journal.

Strickland, W., Journal of a Tour in the United States of America–1794-1795, ed. Rev. J.E. Strickland, 1971. |

|

In October, 1964, an auction at Christie’s in London of a portion of the coin collection belonging to the 4th Baron St. Oswald of Nostell was highlighted by a section containing 30 United States coins struck in 1794-1795. The coins, with a face value of $6.72 were, for the most part, in nearly pristine condition. The announcement of the sale created a furor of interest in the United States, and a number of eminent collectors and dealers made their way across the Atlantic to examine the coins and bid at the auction.

In October, 1964, an auction at Christie’s in London of a portion of the coin collection belonging to the 4th Baron St. Oswald of Nostell was highlighted by a section containing 30 United States coins struck in 1794-1795. The coins, with a face value of $6.72 were, for the most part, in nearly pristine condition. The announcement of the sale created a furor of interest in the United States, and a number of eminent collectors and dealers made their way across the Atlantic to examine the coins and bid at the auction.

Jefferson also consulted with David Rittenhouse [the first Director of the Mint]), to agriculture, to the introduction of the turkey to England. The men parted and maintained a cordial correspondence on all manner of subjects, even after Jefferson returned to public life both as vice president and president.

Jefferson also consulted with David Rittenhouse [the first Director of the Mint]), to agriculture, to the introduction of the turkey to England. The men parted and maintained a cordial correspondence on all manner of subjects, even after Jefferson returned to public life both as vice president and president.

Thirteen years after William Strickland’s return to England, his father, the 5th Baronet of Boynton, died and he ascended to the title. As previously noted, he inherited his father’s varied collections including coins and a library that contained a significant group of works on numismatics and enlarged both. He acquired coins from the tenth century Bossall/Flaxton hoard, which was found on his brother-in-law’s property, and in 1809, he gave a Samanid dirham from the find to the renowned numismatist William Marsden; other coins from the hoard were published in the British Journal of Numismatics in 1960-61, and sold in the Christie’s sale in 1964.

Thirteen years after William Strickland’s return to England, his father, the 5th Baronet of Boynton, died and he ascended to the title. As previously noted, he inherited his father’s varied collections including coins and a library that contained a significant group of works on numismatics and enlarged both. He acquired coins from the tenth century Bossall/Flaxton hoard, which was found on his brother-in-law’s property, and in 1809, he gave a Samanid dirham from the find to the renowned numismatist William Marsden; other coins from the hoard were published in the British Journal of Numismatics in 1960-61, and sold in the Christie’s sale in 1964.